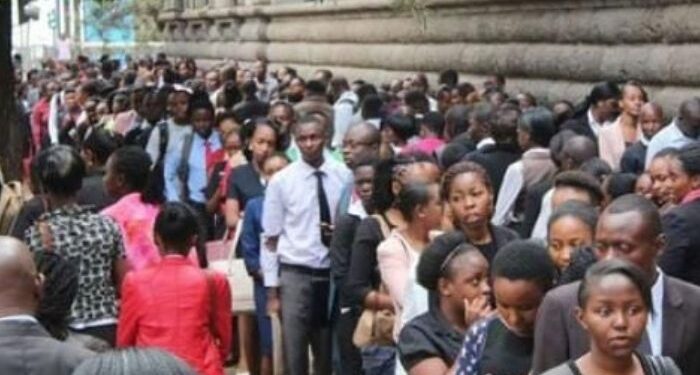

In recent years, Kenya’s Government has increasingly focused on labor export as a strategy to solve the problem of youth unemployment and raise foreign remittances. Over 400,000 young, unemployed Kenyans have secured jobs in countries including Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Poland, and the United Kingdom. While this may seem commendable at first glance, the policy is fundamentally flawed.

Youth, who account for 35% of the Kenyan population, have the highest unemployment rate. The high unemployment has resulted in social and political unrest. It is therefore easy to understand the Government’s push to export labor.

However, labor export creates challenges that can harm the economy. Unfortunately, the drawbacks of the labor export policy receive less attention.

The negative aspects of a labor export policy primarily affect the sending country and its citizens, covering economic and social consequences.

Economic Consequences

The most apparent negative effect of labor export is the brain drain. The emigration of highly educated and skilled workers depletes the country’s human capital. This hinders economic growth and public service quality.

Also, high remittance flows can lead to neglect of the domestic economy. The Government and private sector can be reluctant to enhance domestic industries, mining, agriculture, infrastructure, and social development due to the easy availability of foreign remittances.

The outflow of workers, particularly skilled ones, can reduce labor supply and domestic production. With fewer workers, farms and factories may operate at reduced capacity, directly reducing domestic production.

Not to mention, most of the Kenyans who migrate internationally are talented innovators and entrepreneurs. Their departure can hamper the development of new products and technologies, reducing the country’s overall competitiveness.

Business closures are unavoidable when business owners move abroad, leading to further business exits within the same industry. This causes a ripple effect, reducing local competition and the overall variety of goods and services available to consumers.

Lastly, the departure of workers decreases the total population, directly reducing domestic consumption. In regions with high emigration rates, this can shrink the domestic market for goods and services. And this translates to more business closures.

Social costs

The most severe social cost of labor emigration is family fragmentation. Unfortunately, THE separation of migrant Kenyans from their spouses and children for extended periods often leads to family breakdown. Divorce rates among Kenyans in the diaspora is rising. The trend is associated with challenges for children left behind, including lack of parental supervision, neglect, poor education, behavior problems, and early pregnancy.

The family is the primary unit of society and ultimately of economic production. It also functions as a unit of consumption. Thus, disruption of the family unit can significantly limit economic growth through its negative effects on human capital formation, household stability, labor market participation, and social welfare costs.

Another social cost is dependency syndrome. Individuals and communities who receive remittances become reluctant to seek work or engage in productive activities. This weakens economic growth. Additionally, remittances are often used for investment in non-productive assets like housing, rather than on productive investments that would spur economic growth.

Policy Recommendations

Given the negative effects of labor export, it is imperative for the Government to move away from the policy. The Government needs to pursue sound economic development programs for increased local job creation. Here are key strategic recommendations.

- Establish programs to strengthen families and households, including counseling on financial management and conflict resolution. When the family thrives, it can act as a powerful engine for national economic growth and development.

- Promote innovation and entrepreneurship among young people by providing financial and technical support.

- Reduce taxes, especially on the information sector.

- Support increased investment in the textile industry and other labor-intensive sectors, including agriculture and footwear. The Government should plan beyond AGOA by building domestic markets and focusing on regional markets.

- Intensify efforts to boost value addition to mining and agriculture.

- Ban gambling among the young, and control participation in risky investments.

- Increasing young people’s participation in agriculture to enhance productivity, job creation, and food security.

- Increase corporate-led upskilling initiatives targeting entrepreneurs in all sectors.

Read More: Monetary and Fiscal Policies aren’t enough to fix Kenya’s Economy